INFINITE RED: The Day The Earth Stood Still (2023): My Best Friend is an Electric Box

By Deniz Amasya

Find Deniz Amasya elsewhere: https://falions.net/

I’m not a programmer. I’m not really much of a designer, either. I do know what I like and dislike, though. I really like when my physical relationship to a video game is directly linked to my virtual one. I like when the way I use the controls of a video game are intentional and unwieldy. Killer7, for example, maps its two most common interactions (movement and shooting) to the biggest button on the Gamecube controller, but this is lost in the far more accessible PC version. In the era of multiplatform where “exclusivity” as a concept is functionally dead, it becomes harder to assert this kind of top-down approach to development. This article is about one small aspect of the luxuries afforded to only developing for one platform.

THE GAME, AND THE THING ABOUT IT

I made a game with some friends called Infinite Red. It’s a game I want to be exclusive to a computer forever--the second it enters console space it would become some kind of exhibition piece, a half-baked half-measure about a game that could’ve been, even if it’s the same content.

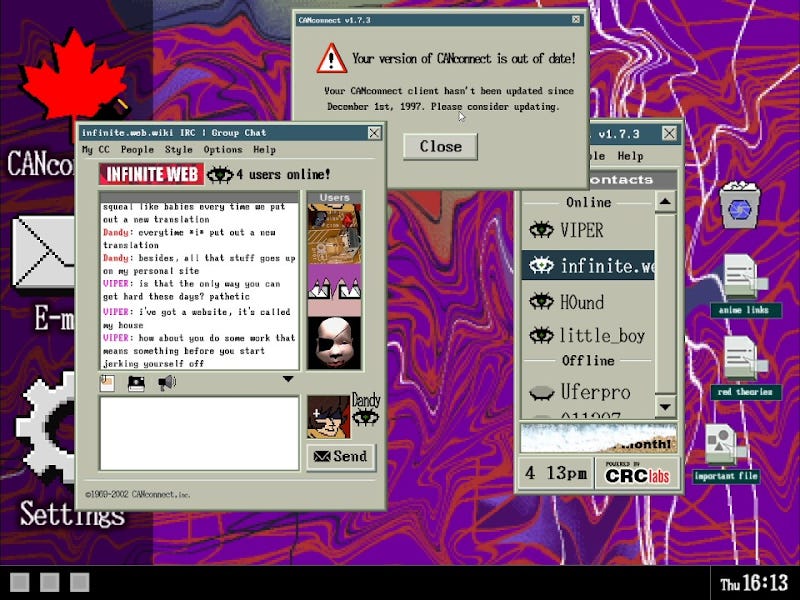

For the uninitiated: it’s a short 15 minute long game about an unfinished video game tie-in to a cancelled 1990s multimedia reboot of a 1970s tokusatsu character named Infinite Red. The first half of the game has you playing the unfinished ROM of Infinite Red: The Day The Earth Stood Still, and once it inevitably crashes you’re led to a virtual desktop of a bunch of fans trying to figure out what the hell they just played was.

In this second half the story progresses in a chatroom environment. A chat window opens up and the characters start to input messages. Other characters’ text is advanced by pressing space, and the character you control--Dandy--is only advanced by inputting random text into the keyboard.

I specifically asked Basement Level, our programmer, to design the text input this way so the player would be going through the same motions as the character. Of course, we don’t press space to advance our own instant messages in real life, but these are the things you have to write off to game-isms that become concessions to suspension of disbelief.

THE ELECTRIC BOX

I’ve spent probably half of my life in front of the electric box called a computer, just as I am now while writing this article. We take a lot of it for granted: it’s this magic machine that shows us movies, music, and yes: video games. But so few video games are keenly aware that they are on a computer, and the ones that do tend to only think about this at a level of how much information is on the screen and how much more efficiently it can be navigated with a keyboard and mouse. The physical lived minutia of using a computer is hardly represented in games made for them, and the simple act of typing into your keyboard and watching text appear on screen made Infinite Red--for me--feel far more alive than had I just let text advance by pressing one button.

Imagine this game being played on a controller, maybe on a television screen. A computer desktop on a large-screen TV is unnatural enough to begin with, but navigating it with a Dualshock? The physical unease of using the hardware alone changes your relationship with the game in a fundamental way. The controller in your hands and the blown-up 800x600 screen on your 50 inch TV is asking you to imagine a world where characters play this video game on their computers as opposed to the inherent immediacy of playing a video game on your computer.

This simple motion also invokes the relationship between the player and the electric box, the thing I’ve spent more time with than my friends, family, and so on, and which was absolutely crucial to the narrative of the game. By creating a kind of mirror it forces the player to reflect on their own relationship with the electric box and its many mysteries. I think this traces back to the thing I realized during the pandemic, that because I couldn’t leave the house I ended up doing all sorts of things on the computer everyday of huge variety: learning Japanese, talking to friends also locked in their homes, discovering genres of music still unnamed by culture at large, and of course, playing video games. All my brain is capable of remembering, though, is that I sat in front of the computer all day--everything I did still happens in a virtual space, just like a video game. That’s exactly why it’s so crucial to really consider how you deal with the 10% of a video game that takes place in reality, because it’s exactly that: real.

And then I log off and I go outside. I get on my bike and pick any direction, wherever seems the most appealing. The corny orthodox rock band I like sounds way better out here than it did locked in my bedroom at 2am. It’s an album I know about because I pressed enough buttons on the computer and it connected me to a band from across time and space. Culturally, historically, geographically removed from me and yet we found each other thanks to my best friend the electric box. Maybe if you press enough buttons in the video game we made, you'll come to your own understanding of why it's so important that the characters found each other, too.

Consider taking the Volume 1 reader survey!